The Peace Movement that Defined the Vietnam War

By: Tim Ford

Introduction

As the Vietnam War raged on in the mid-1960s, more and more Americans joined the anti-war movement. Caught in the global chess game between the United States and the U.S.S.R., the Vietnamese people and their cause became a tipping point for activists who criticized the U.S. government’s involvement in Southeast Asia. Some activists argued for Vietnamese self-determination, while others complained about the high levels of government spending that might be put to better use at home. Unsurprisingly, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), deeply concerned and long interested in the war, would broaden its anti-war activism in the summer of 1967. This campaign would be called “Vietnam Summer.” In accordance with its mission to “promote lasting peace with justice” and “transform social relations and systems,” the AFSC escalated its anti-war activism. As it did so, the broader peace movement gained a momentum that seemed unstoppable. As historian Tom Hayden explained, “no peace movement had ever been as large scale, long lasting, intense, and threatening to the status quo as the protests against the Vietnam War.” This protest would indeed define and set the stage for all future protests. “The 1965-75 peace movement reached a scale that threatened the foundations of the American social order,” Hayden notes, “making it both an inspirational model for future social movements and a nightmarish narrative that our government elites have tried to wipe from collective memory ever since.” The AFSC initiated its protest campaign by canvassing cities all across America. This crucial outreach helped to raise funds and recruit volunteers. In doing so, the AFSC expertly used fliers, ads in newspapers, and posters throughout the country to rally support for the cause. This would be one of the most important accomplishments of the AFSC. Such protest strategies echoed those used by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others in the Civil Rights Movement, while providing a model for today’s movements, such as the women’s rights movement.

The AFSC worked with well-known organizers including economist Gar Alperovitz, former Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) president Carl Oglesby, and the Civil Rights activist, Dr. King. Alperovitz had worked with the United Nations as an economic policy advisor and would play a major role in accomplishing the goals of the AFSC. There is no doubt that he understood the magnitude of the problem presented by this war, and knew that an important way to make a difference was to petition the United Nations to help make a change. Networking with Alperovitz, Oglesby, and King, each a prominent voice in American politics at the time, helped the AFSC’s efforts to publicize the antiwar cause, and lent additional notoriety and respect for the AFSC’s efforts. Moreover, while the AFSC reached upward to prominent political leaders such as Alperovitz, Oglesby, and King, it also reached downward to grassroots supporters to build a firm foundation for widespread protest against the war. These efforts came together in 1967, when the AFSC embarked on its “Vietnam Summer” campaign, a concerted effort to mobilize protests to end the war in Vietnam.

Canvassing

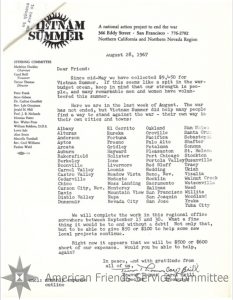

Letter to potential donors and volunteers, from Vietnam Summer Steering Committee members (28 Aug 1967), courtesy of the American Friends Service Committee Archives.

AFSC success in the Vietnam Summer campaign relied in large part on effective canvassing to reach out to individuals who might help with their money or their time. Without such support, the AFSC could not function, let alone promote the Vietnam Summer. Getting people to volunteer was the easy part, as many jumped at the chance to play a part in such a big movement. The harder part was raising money to continue to campaign. To accomplish this, the AFSC printed fliers, placed ads in newspapers, and went door to door talking to people about the horrors of the Vietnam War and what they could do to stop it by getting involved. This recruitment letter lists the cities canvassed throughout California. Efforts like this helped the AFSC mobilize more volunteers, for without people they had no voice. Such mobilization had been seen before with the Quakers and the AFSC, but never on this scale.

Outreach

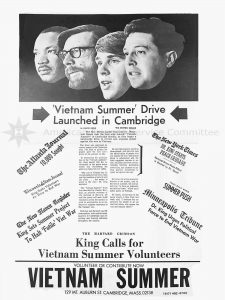

“Vietnam Summer Now in 48 States,” Vietnam Summer News (5 Jun 1967), collections of the American Friends Service Committee Archives.

June 1967 flier calling people to volunteer. Courtesy of the American Friends Service Committee Archives.

The June edition of this AFSC newsletter proclaimed that the “Vietnam Summer [was] Now in 48 states; All Points of View Unite to End War.” The article included three pictures, showcasing Oglesby, King, and Alperovitz at a press conference designed to kick off the AFSC’s campaign. In networking like this, the AFSC worked to connect national leaders with grassroots activists. The article points to ten thousand volunteers who came together in less than three months to work on canvassing, grassroots agitation for congressional hearings, getting referenda on the ballots, and counseling.

In this way, the AFSC aligned “ordinary” Americans recruited via canvassing and posters with movement leaders from a range of fields to make sure that the protest was heard.

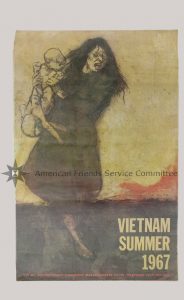

Posters

Posters played a key role, especially in rallying the masses to act. In this poster, the three-color design is carefully chosen to intensify the viewer’s emotional response. Yellow is often used to define hopefulness, but in this instance it portrays the cowardice and deceit of the American government in refusing to acknowledge the innocent victims of the war. The red depicts the fire or napalm that has set the village ablaze, in an attempt to provoke anger and action from the viewer. The ground is painted black, the color of death and negativity, which the artist uses to show that the war must be stopped. To intensify this message, the poster features a woman in the forefront with her two children, who are covered in black soot from the fires caused by the napalm that devastated their village. They appear to be the only survivors of this attack, a lonely yet innocent position that is exemplified by the terrified, helpless expression on the woman’s face. Disoriented, confused, and barely holding onto her children, she flees from the only place she has ever called home.