The methods of entertainment, leisure, and recreational activities of the historic region of the Greater Pittston area have had a major impact on its citizens. Traditions are important to those who call Pittston home. As a mode of building community, networking, and maintaining family relationships, entertainment and other recreational activities are a vital component of social life.

Ann Conroy, a long time citizen of Pittston, elaborates on preferred entertainment and leisure options that found popularity with the people of Pittston. She recalls community dances hosted at St. Rocco’s Catholic Church, going to the movies, ‘people-watching’ in the town square, and sleigh rides. Interestingly, sleigh rides had long been popular in Pittston, as a January 18th, 1856 notice from the Pittston Gazette tells us. Conroy’s memory of sleigh rides points to the ways that entertainment was linked to tradition in Pittston, while other forms of leisure were intrinsically linked to the religious community and public space. These types of entertainment served as a social outlet for those residing in Pittston and the Greater Pittston area. These social outlets kept the town in communication with one another as the people of this time did not have the luxuries that we have today, such as Facebook, Myspace, or Twitter, making these events much more crucial to keeping in contact with friends, family, and peers.

Early forms of live entertainment flooded into the local theaters throughout Pittston, as well as surrounding borough venues. Blackface minstrelsy, for example, was an exaggerated representation of African Americans through the practice of using black make-up applied to the actor’s face, who then performed a show imitating African American styles of dance, music, and speech. Throughout the US and into the mid-twentieth century, small cities like Pittston still expressed interest in Blackface, as can be seen in a Lukasik Collection photo below. After the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, popularity for Blackface minstrelsy reached its demise, making Blackface an obsolete and distasteful form of entertainment.

Sporting events also served as a form of entertainment and community-building to the citizens of the Greater Pittston area. The 1976 basketball season had provided a Pittston Area high school basketball player, Joseph Yanchis, the opportunity to showcase his talents. Joseph Yanchis, like other student athletes, could generate such excitement and anticipation in small owns such as Pittston. The opportunities to watch live sports were scarce. High School sports, which still holds much popularity today, held even more popularity during this time due to the lack of nationally broadcasted sports on the television networks. If a person wished to see a basketball game, a person would maybe be able to catch a game on television once in a great while. By attending these small town games, sports fans would follow a team throughout an entire season, even being able to follow their local high school team to away games due to the close proximity of the venues.

Yet it was not just the athlete who benefited from this athletic form of entertainment. The people of Pittston flocked to these competitions and even completely filled their venues. One of the most popular venues that hosted multiple Pittston Area basketball games (including the championship game) was the famed Catholic Youth Center (CYC) located in Scranton, PA. Yet basketball was not the only source of entertainment that the CYC provided; the CYC provided the citizens of Northeastern Pennsylvania with various entertainment options such as professional wrestling, boxing, and concerts all hosted at this legendary venue. Originally a religious-sponsored community center, the CYC became an iconic venue for numerous social and athletic events. As a center for entertainment and leisure in the Pittston area, the CYC became integral to the community for multiple generations, who continue to associate it with fond memories of community activities in Pittston’s past.

Through all of these community gatherings, sporting events, and social outlets, the people of Pittston experienced leisure in a way that complemented national trends in American culture. Their leisure and entertainment activities became embedded in the fabric of social life, and served to link the residents of the Greater Pittston area with their counterparts nationwide.

—Mike McDonnell

Ann Conroy’s Sleighing Parties

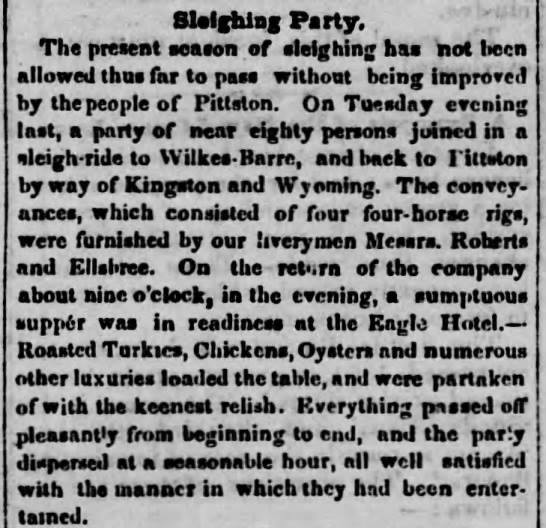

Caption: “Sleighing Party,” Pittston Gazette (January 18, 1856), Collections of the Greater Pittston Historic Society, Pittston, PA.

This is an article from the Pittston Gazette covering a sleighing party followed by dinner at a local hotel. Over eighty people from the Pittston area were pulled by horse-drawn sleighs through Wilkes-Barre, Kingston, and Wyoming, Pennsylvania, and back to Pittston. One hundred years later, individuals continued to enjoy sleighing parties in Northeastern Pennsylvania. In fact, sleighing parties were held all over the US in the 1950s. From Abilene, Kansas, to Titonka, Iowa, to different parts of Pennsylvania like Lock Haven and Pottstown, sleighing parties were a prevalent form of entertainment. In all of these events, large groups, friends, and families would gather, sleigh, and enjoy a dinner at a local hotel. As Ann Conroy remembers:

“–and then I remember sleigh riding on Johnson Street… all the parents came out and celebrated. We started up there on Johnson Street and we came all the way down here to the mine… It was hard walking up [laughing] one day I remember the city came up and put ashes down we all got our brooms and swept the whole [laughing] street… So, we swept the whole street and started sleigh riding again.”

Interestingly, this article is from nearly one-hundred years before Pittston resident Ann Conroy lived, and sleighing parties were still considered a favorite pastime. Conroy tells us that when the city poured coal ashes on the streets to melt the snow, a seeming obstacle to the youths’ fun, they banded together with their brooms and swept the streets clean. Then, they sleighed.

Pittston teens in the 1950s enjoyed television, music, and the movies, like their national counterparts in cities across the US. Yet Pittston of the early postwar period, however, was a city of its own. Dances weren’t held at the schools; instead dances in Pittston were usually held at the local church of one’s ethnic group. Ann tells us about dances at St. Rocco’s church. Ethnic churches, like St. Rocco’s, were important institutions for immigrant communities in the early twentieth century. Likewise, Pittston teens also found entertainment in places like the American Theatre, and even the town square. Conroy recalls driving down to the main square and watching the passersby. Sometimes she would even get a nickel to buy a sweet.

Culture involves those traditions, like sleighing parties, passed down from generation to generation. Traditions are not just the foods we eat, or the music we listen to, or marriage practices. Pastimes, or how each generation entertained themselves, are equally as important. Yet as this article and Ann Conroy’s oral history show, even as Pittston residents set themselves apart from some of the most popular national trends, even the smallest of towns can be connected culturally and otherwise to the broader United States. The sleighing party is one cultural institution that connects Pittston’s past to the present.

—Nicole Negron

Controversial Performances

Blackface Minstrelsy Performance, c.1950-1965. Lukasik Studios Collection (5000.1.1318), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

This photograph is from the Lukasik Collection at the Greater Pittston Historical Society and depicts a Blackface minstrel performance. There are several adults on stage with three men in Blackface make-up and exaggerated clothing. The photograph is not dated, but the clothing suggests the 1950s. The audience consists of mostly children and young teens. The production took place at Holy Rosary School in the Duryea borough of Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Blackface minstrelsy began with the comic routines of Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice in 1828. Between 1840 and 1890 it was the most popular form of entertainment in America. Blackface minstrelsy consisted of the characterization (typically through caricature) of plantation slaves and free blacks, and the imitation of African American styles of music, dance, and speaking. By 1919, there were only three major troupes who performed blackface minstrelsy, but the minstrel show continued to flourish in small towns. In fact, there was still an abundance of blackface minstrel shows in major US cities in the 1950s. For example, in 1950 the Daily Herald of Chicago advertised a Blackface minstrel show as “Aunt Jemima to bake ‘Little Black Sambo’ pancakes Monday.” Catering to a middle-class, white (and largely Protestant) audience, such shows belittled African Americans and other minorities. Moreover, discrimination practices against Catholics, Jews, and African Americans persisted in the postwar decades—not just in the American South, but across the US and in many northern cities.

By the time this photograph was taken, Luzerne County had undergone half a century of population growth and industrial expansion. There were major cultural changes — many related to the booming mining industry — as an influx of immigrants arrived and established ethnic institutions, athletic clubs, fraternal organizations, and churches between 1920 and 1960. Luzerne County was considered one of the most ethnically diverse regions in the US between 1920 and 1950, but the African-American population remained relatively small in the area.

According to Luzerne County Census data for 1950, there was a total population of 392,241 in Luzerne County, 929 of which were African American, five of which lived in Pittston. While many of the other immigrants to the area formed fraternal organizations and ethnic-based parishes as community support institutions, Pittston did not have any African-American churches or other community-based organizations for blacks in these years. Luzerne County’s highest density of African Americans was in the city of Wilkes-Barre, and unsurprisingly this is where the abundance of black-owned and led churches had their start. Without a large African-American population, Pittston would have remained insulated from the cultural and social changes associated with Civil Rights and black activism in the 1950s and 60s, such as the labeling of blackface minstrelsy as an offensive form of entertainment.

As the mid-twentieth-century Civil Rights movements gained momentum, the minstrel show categorically died out in the US. However, we can still see smaller forms of its characteristics in modern entertainment today. Blackface minstrelsy often seems shocking and distasteful to today’s viewers, who in hindsight see the representations as offensive caricatures. This is largely because of the cultural changes wrought by the mid-century Civil Rights movement. While many Americans understand the political and social changes brought by the Civil Rights movement — in ending voting restrictions and segregation, for example — the cultural changes brought by this movement are often more difficult to perceive. This image from the Lukasik Studios Collection points us to a moment before the widespread changes of the Civil Rights movement, which categorically rendered Blackface entertainment as offensive. What we gain then, from this image, is a clearer picture of how the Civil Rights movement reshaped American culture — and specifically, entertainment — to cause the rapid decline of blackface minstrelsy in local communities and change individuals’ perceptions.

—Nicole Negron

Pride in the Pittston Patriots

A High-School Basketball Game Between the Pittston Patriots and the Lackawanna Trail Lions, Scranton, PA (1976), Sunday Dispatch Photographic Collection (1976.1.1101), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

This image shows two high school boys’ varsity basketball teams from 1976 playing a game at the Catholic Youth Center (CYC) in Scranton, PA. The away team, wearing the dark colored uniforms, is Pittston Area High School (Patriots). The home team (in white) in this image is Lackawanna Trail High School (the Lions) as the words “TRAIL,” can be made out by increasing the magnification and observing the player just left of image center. The key, in basketball, refers to the markings on the floor beneath the basket. The viewer can see four players, three from the home team and one from the away team, standing in the key in this photograph.

Looking just slightly above image center, the viewer can observe a Pittston Area player taking what seems to be about a twenty-three foot jump-shot while being defended by a Lackawanna Trail player. The Pittston player taking the shot is Joseph Yanchis, wearing number forty-five. While Yanchis’ shot would appear to be a three-point one for today’s viewer, high-school basketball leagues did not implement the three-point scoring option until 1987. Though the shot Yanchis took still only counted as a normal basket, it is impressive to see Yanchis’s ability to score from this distance on the court. Joseph Yanchis was an important player in this specific contest as footage of this game can be seen on youtube.com.

This photo captures the importance and love of athletics across the Greater Pittston area. Sports, athletics, and competition are part of the traditions of Pittston extending throughout all of Northeastern Pennsylvania from the Wyoming Valley to the Pocono Mountains and beyond. Players like Joseph Yanchis could create such excitement throughout towns such as Pittston. Looking at the bleachers, the viewer can easily notice that the stands are completely packed with spectators, most likely a sold out crowd.

High school basketball reached an all-time high in popularity throughout the 1970s, especially given the reduced television coverage of professional games at the time. In the mid-1970s, the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the former rival league known as the American Basketball Association (ABA) merged together to all play under the flag of the NBA. This did not sit well with the fans, as the NBA’s contract with the ABC television network did not renew. The NBA contract was eventually picked up by CBS, but CBS did not promote the NBA with the same enthusiasm that ABC formerly did. Other sports that ABC broadcasted, such as football, dominated the prime time slots contributing to the popularity loss. With the tight iron-clad grip that the networks held on the NBA, people flocked to these high school amateur games as it was, at the time, the only consistent way to participate in a basketball season.

—Mike McDonnell

A Venue for the Ages

Pittston Area High School vs. Unknown Opponent (1976), Scranton, PA. Sunday Dispatch Photographic Collection (1976.1.1102), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

This is an image of a 1976 high school boys’ varsity basketball game featuring the Pittston Area High School Patriots and an unidentified home team. Since there is no visible team name on the home teams’ white jerseys, we must look to the venue to identify possible home teams. From the large stands in the background, the architecture of the wall, and the skylights on the right side of the image, we can identify the venue as the Catholic Youth Center (CYC) in Scranton, PA. The home team could thus possibly be old Scranton Central High School or Scranton Prep High School, both of which used the CYC as their home court during the 1970s. Basketball is not the only event that this legendary venue hosted. The CYC has been known to host professional wrestling, boxing, and concerts as well.

The CYC was built by the Diocese of Scranton in 1949 on the location of the former John Jermyn Family Home. The building’s architecture is built in the Art Deco style and is located in Scranton’s Lower Hill District at 500 Jefferson Avenue. In addition to hosting home games for Scranton area schools, Pittston Area High School also played at this venue during the 1960s and 1970s in championship games: for over sixty years, the CYC was the home of conference and district championship games for the Wyoming Valley and Lackawanna Athletic Conferences. The CYC thus became a staple of social life in Pittston; it is the venue many parents and former athletes remember when recalling High School championships. One of the most notable appearances for the Pittston Patriots came during the 1977 season where Scranton Central High School beat Pittston Area High School by a score of 72-59 in the championship game.

The CYC contributed to the glory of Northeastern Pennsylvania athletics as it hosted fifty-nine boys’ varsity championship games, dating from 1951-2009. The CYC also hosted seven girls’ varsity championship games during the new millennium from 2003-2009, totaling sixty-six championship games in all.

The CYC is a massive venue that could accommodate up to five-thousand seats. The CYC still stands today, however this massive venue was relieved of the famous CYC name on February 14th, 2004 and is now the Lackawanna College Student Union (LCSU). Still a center for sporting events, the venue now hosts Lackawanna College Falcons basketball games.

—Mike McDonnell

Sources:

Ann Conroy Oral History, 30 Oct 2013, interviewed by Mary Policare. Collections of the Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

Zbiek, Paul J., and Sally Teller Lottick. Luzerne County: History of the People and Culture: An Illustrated History. Wilkes-Barre, PA: Wyoming Historical and Geological Society, 1994.

“Aunt Jemima to Bake “Little Black Sambo” Pancakes Monday.” Daily Herald (Chicago, IL), November 10, 1950. Accessed July 22, 2015. http://www.newspapers.com/image/44511004/?terms=blackface.

Moss, Emerson I. African-Americans in the Wyoming Valley, 1778-1990. Wilkes-Barre, PA: Wyoming Historical and Geological Society and the Wilkes University Press, 1992.

http://thetimestribune.com/sports/lynetttournamentalookbackat60yearsofexcellence

www.usab.com/youth/news/2011/06/the-history-of-the-3-pointer.aspx

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JxxT3nGZwTM