The people that migrated to Greater Pittston came here to work because the coal mining industry was booming in the early twentieth century. People of all different ethnicities settled into different neighborhoods of Pittston and established language-based churches and synagogues.

Churches and religion played a major role in the everyday life of the families in this area. As Helen Brigido says in her interview with the Greater Pittston Historical Society, “We were taught religion early. We were taught to respect our neighbor and we were taught to watch our neighbors’ goods.” This is important because people living in Pittston at mid-century made sure that family came first and every Sunday they would be at church. Helen lived her life this way. She had very close relations with her brothers and she would go with her brothers everywhere. Churches were incredibly important for the local community; they hosted events that brought the congregation together, and many of the churches would sponsor elementary schools to educate the children of the parish. Many of these Catholic schools are still open today, such as Holy Rosary School in Duryea, PA. Churches also held annual festivals where people of the community would come together and support the parish financially. Finally, Ann Conroy mentions in her interview with The Greater Pittston Historical Society that Saint Rocco’s would hold dances in their school hall for the younger members of the parish to spend time together. For all of these reasons, the church was a central fixture of social life in Pittston in the postwar years.

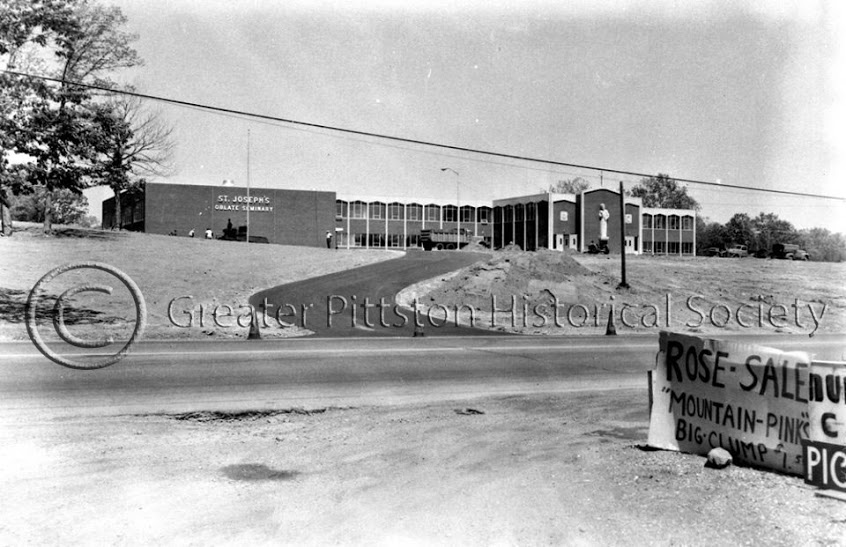

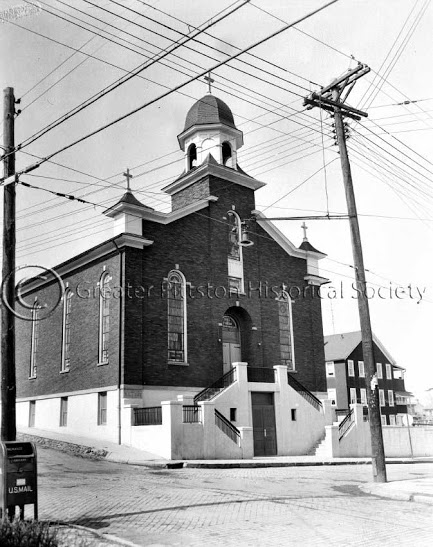

The Oblates of Saint Joseph, in Laflin, PA. Collections of the Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

The Catholic Church in the area has seen a decline in enrollment since the 1990s. Father Dan Schwebs attributes this to the younger people, who once made up a majority of the population of the church, having since moved away. Due to the decline in church-goers many parishes have been forced to close and combine with other parishes. Sacred Heart, Saint Joseph’s, and Holy Rosary in Duryea have combined to form Nativity of Our Lord Parish. Saint Joseph Morello Parish in Pittston is a combination of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and Saint Rocco’s parishes. Saint John the Evangelist gained the members of Saint John the Baptist, Saint Casimir’s, and Saint Joseph (Port Griffith) in the early 1990s.

While the Roman Catholic Church had a strong following in the area, there were also different religions with strong connections to area. The Polish National Catholic Church was founded in the northeast region of Pennsylvania in the late 1890s and still remain in the Greater Pittston area, including Holy Mother of Sorrows in Dupont and Saint Mary’s in Duryea. The Polish National Catholic Church was founded because of disagreements between the immigrants and the leaders of the church. Father Dan talks in his interview about how many immigrant groups were not necessarily accepted by the church: “If you remember in 1929, there’s a big Italian Immigrant population here in Pittston, and the immigrants were not always welcomed in some places so as a result …they established three Protestant churches here in Pittston. There was the Presbyterian Church which was Saint Joseph’s.” Moreover, Ronne Kurlancheek mentions that in

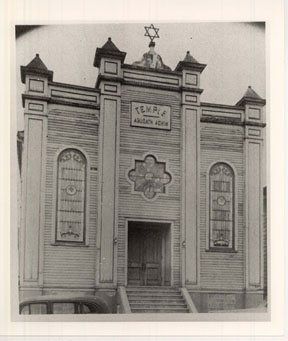

Temple Agudath Achim, meaning “society of brothers,” which was located on Broad Street in Pittston (now the site of Child Jesus Traditional Catholic Church). It was merged into Temple Israel in Wilkes-Barre in 1980. Image courtesy of Dr. Daniel Weisberger.

Duryea there was a small group of Orthodox Jewish peoples who established a synagogue there on Newton Street.

Religion provided a focal point for family life, structuring holidays, gatherings, and other rituals that linked family members together to worship and socialize. As Ronne Kurlancheek tells us, for the region’s small Orthodox Jewish population, religious practice brought the community together and fostered interconnections between the parish’s families. In this way, the church served to strengthen community bonds. For other groups, however, internal strife within the church led to community fractures. As Father Dan reminds us, the Polish community eventually established their own Catholic branch when communication between church leaders broke down. The families of the Greater Pittston area used religion and the bonds of their family members to make it through everyday situations. These families had their troubles but their faith and family guided them through.

— A.J. Mancini

Religious Ritual

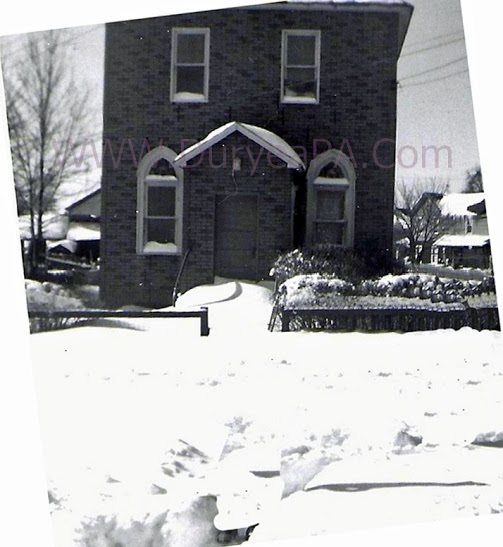

Orthodox Jewish Temple, Newton Street, Duryea, PA (undated). Image Courtesy of Mike Lizonitz and DuryeaPA.com

“…as far as the temple, there was a small orthodox temple in Duryea, believe it or not. It was on a side street in what was originally a house, and it was an orthodox temple which means that the women sat upstairs to pray, and the men sat downstairs, and it was only open for the high holy days… I do remember walking there, for years…”

Ms. Ronne Kurlancheek recounted that there were between ten and thirteen Jewish families in Duryea. In 1920 these families founded the Keneseth Israel Congregation. Her grandfather, Jacob Kurlancheek, was one of the original charter subscribers. The photograph above is the Duryea synagogue, located on Newton Street.

In the late-nineteenth century, and due primarily because of religious persecution by the Russian Empire, many Lithuanians, especially those of the Jewish faith, sought refuge in the United States. According to Ronne, the Kurlancheek family arrived from Lithuania in approximately the year 1890, and originally settled in the Carbondale, Pennsylvania, because they had family members there. This was a common practice for newly-arrived immigrants of the time.

Ronne recounts that her grandparents, Jacob and Sadie, moved from Carbondale to Duryea shortly after their arrival in the United States. They opened a small hardware store on Main Street in 1898.

As practitioners of the Orthodox Jewish faith, they sought a place to worship in closer proximity to their home and business. This desire to have an Orthodox synagogue within walking distance inspired the Kurlancheeks, and other Jewish families in the Duryea area, to create a chartered congregation, and to buy the Newton Street residence to serve as their temple.

“…we would walk to temple, and that’s why it was important to have a temple in Duryea…”

High Holy Days had required customs, especially for Orthodox Jews, such as the Kurlancheeks.

As Ronne elaborated:

“…the entire family went to my grandmother’s [Sadie Kurlancheek] house, because for the high holy days you didn’t… turn on or off any electricity… or drive [automobiles]…”

Ronne recalls her family gatherings during these religious holidays, and the traditional Lithuanian Jewish food which her grandmother made.

I remember us all being together at my grandmother’s house and celebrating, and she was a wonderful cook. She made her own pickles…grape jelly… [and] pickled herring pies, which really goes back to Lithuania.

Looking back on her family’s commitment to religion over the years, Ronne concluded:

Gravestone of Jacob Kurlancheek, Ronne’s grandfather.

Image Courtesy of Mike Lizonitz and DuryeaPA.com

“…my grandparents were very religious, and I think that’s very typical when an immigrant comes, they’re very religious, the kids are a little bit less, so. That’s probably the American story.”

As immigrants fleeing their homeland in Lithuania due to religious persecution, the Kurlancheeks were able to settle in a predominately Roman Catholic community within the United States which welcomed them, unlike the Russian Empire. The town of Duryea, in particular, encouraged the Kurlancheeks to flourish within both family and business life, which resulted in their being held in high regard and becoming pillars of the local community.

–-Patrick Gallagher

Immigrants

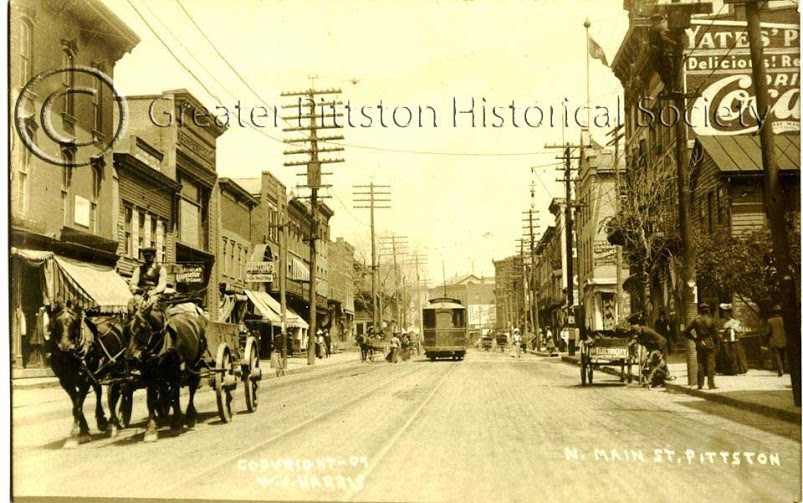

Main Street in Pittston, c.1900. Collections of the Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

In the early twentieth century, thousands of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe came to the United States in search of opportunity. Though many of these individuals were unskilled laborers, they possessed a strong work ethic and a loyalty to their community that would serve them well in their new home. Throughout the country these people worked hard jobs for low wages. Italians made up a large number of the immigrants coming to the US, and worked every kind of job possible. In New England they worked in stone quarries, in the mountains of West Virginia they would work in the mines, and throughout every corner of the country Italians would work on farms. At the turn of the twentieth century, Southern Italian immigrants were among the lowest paid laborers in the country.

Helen Brigido’s parents came to Pittston from Naples, Italy, around 1918—after World War I had wrecked the Italian countryside and its economy. The process of emigrating was often difficult and filled with challenges, even for those immigrants who had family members and shelter waiting for them in the US. As Helen mentions, her parents traveled through rough weather across the Atlantic to come to the US, but before they could enter the country they had to prove they had sponsors in America who would secure them a home and employment. Sponsors often also support immigrants financially, making resources available if the immigrant needed them, and helped to make sure that immigrants would be active members of society. Helen’s family found their home among the thriving Italian community in Pittston.

Growing up, Helen remembers the tight-knit community of family and neighbors:

“We were very, very close. We never had any friends because I had my brothers and my sisters. That’s all we had, and we loved one another. … My mother was very strict with me because my two sisters were married and my brother had to take me with him wherever he went. Must have been kind of embarrassing, but I didn’t think anything of it, and he didn’t either; he was just glad to have me. We had a wonderful relationship. I played with my brothers, not so much my sisters, but my brothers who were closer to my age… but we had a wonderful, wonderful childhood.”

Helen’s family only spoke Italian, and she recalls the obstacles she experienced in school because she didn’t know English. As she learned the language, she began to better understand the school subjects. By the time she was in high school in the 1930s, Helen was fluent in English and took a job working in a shoe store in town as a sales clerk. Though Helen was quick to note that life in Pittston has changed greatly since she was a girl. For example, before the sharp rises in inflation in the 1970s, soda was only 5 cents at the local store.

Like many immigrants to the Wyoming Valley, Helen’s father gained employment in the mines. Helen talks about times when her father would come home from work and he would be so dirty from the mines that all she could see was the whites of his eyes. Her father was an only child and never imagined working as hard as he did when he came to the States:

“He didn’t think that when he came to America he would have to work so hard. He was an only son and of course he was tutored my grandmother had private tutors for him and he said he didn’t think it would be that hard. But he stuck it out because he had a family and he didn’t say too much but I could remember him coming home and all you could see was the white of his eyes.”

Today, as in the 1900s, many immigrants face difficulties in the country. Like Helen’s family many immigrants face trouble assimilating into the culture, and tend to work jobs for low wages. These men and women of today, like Helen’s father, understand that they must work hard to continue to support their families.

— A.J. Mancini

The Polish National Catholic Church

First Communion at Holy Mother of Sorrows (PNCC) in DuPont, PA, 1961. Lukasik Studios Collection (5000.1.0543), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

The image to the left shows a First Holy Communion from 1961 at Holy Mother of Sorrows Polish National Catholic Church in DuPont, PA. The Polish National Catholic Church was born in nearby Scranton in 1897, out of ethnic strife and misunderstandings between the Irish bishops and the Polish congregations and some clergy. Similar situations arose in Buffalo, New York, and Chicago (both Buffalo & Chicago would ultimately merge with the Polish National Church).

Prime Bishop Franciszek Hodur was the leader of the Polish National faction, having been the pastor of Holy Trinity Church in Nanticoke (and bringing peace during a period of ethnic strife there), and Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Church in Scranton, both part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Scranton. His congregation at the Scranton church felt they were not represented well by the Irish bishop of Scranton, and believed it was the right of all ethnic groups to say mass in their own language, as opposed to Latin. With (then) Father Hodur’s assistance they broke away and founded St. Stanislaus Church (now Cathedral) in Scranton, the Mother Church of the Polish National Catholic Church.

Holy Mother of Sorrows Church in DuPont, arose out of a conflict involving the parish priest of Sacred Heart of Jesus Church, also in DuPont. In the 1916, the priest, Father Edward Gucwa, was at the heart of a split in his congregation: half the parishioners wanted him removed, half wanted him to stay. As stated by scholar Rev. John P. Gallagher, Ph.D., “Attempts by the trustees to dislodge him from his possession of the rectory met with failure. The bishop then ordered him to leave, but the command fell upon deaf ears.” And lines were drawn between those in opposition and those in support of Father Gucwa. Rev. Gallagher goes on to say, “In the aftermath, Father Gucwa was jailed on the complaint of the trustees, was found guilty by the courts, and was legally banished from Luzerne County forever.” Father Gucwa would ultimately be recruited by Bishop Hodur to serve the Polish National Catholic Church outside Pennsylvania. Out of this chaos, Holy Mother of Sorrows Polish National Church was born in 1916.

There would be trouble though, between the two congregations for a long while. John Gromala, resident of DuPont, recalls,

“My uncles told me stories of the Polish National-Roman Catholic split in DuPont. For a long time, the two groups wouldn’t associate with each other at all, or if they did, it was violent encounters. The Catholics took to calling the Polish Nationals “kickers” as a slur, as in our minds, they’d been kicked out of the church and had to go start their own. They called us “suckers” for the way we blindly followed the bishop. There were some exceptions to this animosity, such as when the Sportsmans’ Association built a campground and pond up in Suscon. Catholics and Polish Nationals were part of the effort. By my time [1950’s-1960’s], things had died down, and while we didn’t associate much with the Polish Nationals, there wasn’t the outward animosity and problems that there had once been.”

The children in this image, celebrating the sacrament of First Holy Communion, point us to some of the doctrinal revisions made by the Polish National Catholic Church when it separated from the Roman Catholic Church. While the PNCC and Roman Catholic churches share theological doctrine, in practice the churches follow different policies governing clergy, parish property, and confession. Polish National priests are allowed to marry and raise a family, as opposed to the celibate Roman Catholic clergy. Also, in the PNCC parishes hold independent control over parish property: it owns the property and can hire and fire priests, as opposed to the Roman Catholic dioceses controlling these things. The issue of papal infallibility was also a point of contention. The Prime Bishop of the PNCC is not considered infallible, as opposed to the Pope. Finally, while the Roman Catholic Church requires individuals to complete the sacrament of confession at multiple times throughout their lives, the PNCC only requires personal confession on one occasion, and that is for children seeking first Holy Communion. The children shown here have been officially anointed into the PNCC. The large size of the Communion class demonstrates both the persistent commitment of the local residents to their faith, and the draw of the PNCC for the local Polish community. As an organization founded by immigrants who felt marginalized by the Roman Catholic Church, the PNCC thrived in the Pittston area by supporting the faith of the local community. It has remained a prominent fixture of religious life ever since.

— Matt Gromala

Church Consolidation

Before the 1960s, the Protestant faith was the dominant religion in the US, with very few Jewish and Catholic voices heard in the national conversation. After a slight decline in church membership during the 1920s, a new wave of religious fervor came in the immediate years after World War II. Members of the middle classes moved into the suburbs and established new parishes, and church attendance grew. The church became an integral part of the middle-class household, and a central component of family life.

The removal of the Protestant Religious hold on the country was intensified by Catholic ethnic groups migrating into communities together. Father Daniel Schwebs talks in detail about how the parishes in the Greater Pittston area were founded by the immigrants coming into the area.

“The reason why in the United States especially, especially in the northeast, that we have so many ethnic parishes than the west … is because immigrant groups to the United States and they were looking for places to worship. And sometimes there was misunderstanding because people are just that way, and the ethnic groups wanted to keep their languages alive and their customs.”

Saint Rocco’s Church (undated). Mike Savokinas Collection (MS0000.1274), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

Local parishes formed along ethnic lines continue to persist to the present day in the Pittston area. The parish of Nativity of Our Lord in Duryea still has a strong Polish ethnicity in their congregation; Saint Joseph Morello in Pittston, formerly known as Our Lady of Mount Carmel, has a strong Italian following; and before its closing Saint Rocco’s in Pittston had a strong Sicilian following. Along with the Roman Catholic parishes being founded other parishes were also founded, often due to disagreements happening between the church and groups of immigrants. One of these major parishes is the Polish National Catholic Church. Two of the PNCC churches are still operating in the Greater Pittston area: Saint Mary’s Polish National Catholic Church in Duryea and Holy Mother of Sorrows in DuPont. Along with the Polish National churches there was also Baptist churches, Methodist churches, and also small synagogues.

By the 1960s things began to change, in the broader US, as the Civil Rights movement and questions over the Vietnam conflict came to the forefront of American life. These events made the young people of the 60s generation question their faith and dominant church establishments.

The Pittston area has also seen the decline of churches happen. When the first generation of immigrants became too old and their children began to move away, churches began to close. These churches were not financially stable and were forced to close their doors and merge with other churches to survive.

In terms of religious growth and contraction, the Greater Pittston area thus paralleled the national trend. Both nationally and locally immigration played a major role in the formation of churches. While in the 1960s the Catholic Church went through hard times because of the younger generation questioning the establishment, in today’s time, locally, we see the younger generation moving away and creating financial hardships upon the church.

— A.J. Mancini

Sources:

Gallagher, Rev. John P. A Century of History: The Diocese of Scranton 1868-1968. Scranton, PA: The Haddon Craftsmen, 1968.

Levin, Marjorie. The Jews of Wilkes-Barre: 150 Years (1845 – 1995) in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Jewish Community Center of Wyoming Valley, 1999.

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/twenty/tkeyinfo/trelww2.htm

http://www.immihelp.com/affidavit-of-support/sponsor-responsibilities-obligations.html

http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/italian7.html

Mining the Past Business & Industry Entertainment & Leisure Patriotism & Politics