Mining the Past:

Family, Faith, and Industry in Postwar Pittston

Business & Industry Entertainment & Leisure Patriotism & Politics Religious & Family Life

Exhibit Introduction

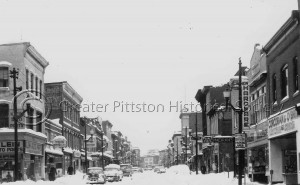

Main Street Pittston, c.1950. Mike Savokinas Collection (MS0349c), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

With the end of the Second World War, the United States saw a growing economy which had rippling effects for American society and culture. The rationing and sacrifice of the people at home was no longer necessary as the US became an official superpower. The end of the war also brought a slow growth of wealth. After the Depression and World War II, the average family could afford the luxury of an automobile, which was one of the leading causes of suburbanization. People could afford a more reliable commute to work and had the means and the motive to leave big cities. With all of this postwar growth, there was also a move away from primary economic activities and small (typically family-owned) business towards the department store and the superstore.

The men returning from war, beginning in 1945, came home ready to marry, settle down and have children. The resulting “boom” in the American birthrate also fueled a return to traditional values and gender roles, as returning soldiers went back to work and women, who had replaced men in factory jobs and support services during the war, returned to the home as housewives.

According to the Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History, America’s diverse group of immigrants utilized religion as a means of holding on to their native customs immediately after World War II. As the decades progressed, white ethnics turned away from the traditions and identities they’d held onto so tightly before the war, in an effort to become more “American,” as historian Matthew Frye Jacobson notes. This eschewing of ethnic tradition was matched by a similar turn away from religious practice. By the late 1960s and 1970s, the US became increasingly secular. This decline was shown in lower church attendance, fewer additions to the priesthood, and the questioning of religious institutions / faith, partly due to Vietnam and the violence of the Civil Rights movement.

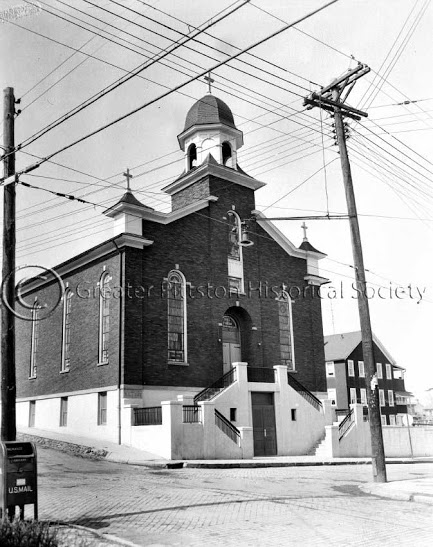

Saint Rocco’s Church (undated). Mike Savokinas Collection (MS0000.1274), Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA.

In contrast to the trends at work in the larger US — especially in the areas of suburbanization and secularization — Greater Pittston followed a different path. Social and religious life for people in Greater Pittston was utterly interdependent, and demonstrates a paradigmatic shift from that of the national trend. Immigrants from Lithuania, Ireland, Poland, Italy, Germany, and many Jews from throughout Eastern Europe migrated to Northeast Pennsylvania and especially to the Greater Pittston area. They worked in the lucrative coal industry, and later started small businesses of their own that would serve the area for years. Once they were here they organized local, ethnically-based parishes to serve their social needs as well as to hold on to their native cultures, especially language and religious customs. It was through the parish that athletic clubs, fraternal organizations, and dances for the local teens were started in Pittston. Other religious organizations such as the Catholic Youth Center (CYC) held many athletic events for Greater Pittston area sports teams.

The Greater Pittston area resisted the national trend of secularization, as parishes here flourished, and religion remained the centerpiece of the family. This is evident in the oral histories of Ronne Kurlancheek and Father Daniel Schwebs. By the 1980s and 90s, however, parishes began closing and / or merging.

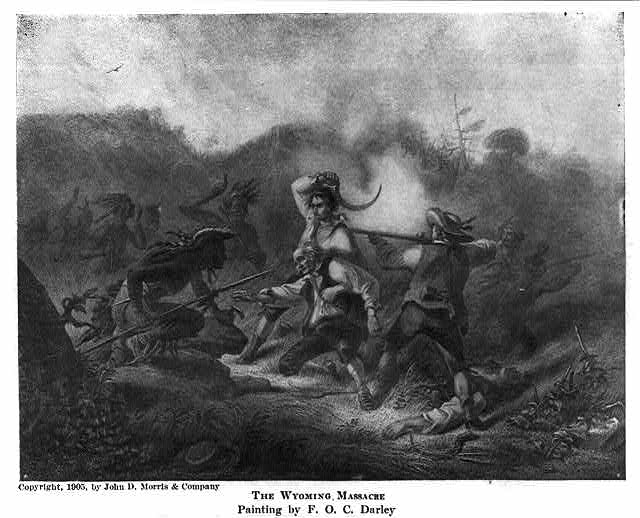

Residents of the Wyoming Valley have long remembered the valor and sacrifice of their ancestors in the Battle of Wyoming, as shown here in this 1905 artist’s rendering from the Library Congress, titled “The Wyoming Massacre”. Halftone repro. of painting by F.O.C. Darley, copyrighted by John D. Morris & Co. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, (reproduction number LC-USZ62-79876). http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b26874

Greater Pittston is an area steeped in a rich and proud history, as well as a heightened sense of duty and patriotism, much of which stems from the region’s involvement in the American Revolution. In 1778, while the majority of the Wyoming Valley’s able-bodied men were away fighting under General George Washington for the Continental Army, an overwhelming force of British and their allies befell the thinly defended forts all along the Susquehanna River in what is now known as the Battle of Wyoming. This surprise attack resulted not only in a tremendous military defeat for the small local militia, but also an ensuing massacre upon all but four captured militia men who had surrendered. During the 1976 bicentennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Greater Pittston, like many other cities in the US, held enormous celebrations and parades to commemorate that event, as well as the contributions and sacrifices of the region’s early settlers in the War for Independence.

Yet in other ways, business practices in Greater Pittston ran counter to the national trends of the time. Several women in the Greater Pittston area were involved in business management and ownership during periods of the twentieth century where the national trend was yet resistant to women being anything other than housewives. In this respect, Greater Pittston was ahead of its time. The Greater Pittston area also resisted the development of very large shopping malls — maintaining small business districts, as well as individual shops, at a time when many similar districts across the US had succumbed to larger retail giants and department stores. Small, family-owned, businesses were the binding fabric of downtown Pittston for many years, lasting for an additional twenty or thirty years beyond the national average. Some of these small businesses have adjusted and adapted and continue to exist to this very day.

The loyalty toward, and accommodation of, local businesses in Greater Pittston stemmed from the welcoming attitude of the people. Greater Pittston was accustomed to waves of immigrants having arrived over the past two centuries. A steady stream of immigrants allowed the local people (who were mostly immigrants themselves) to to accept and tolerate new and different peoples, and actually welcome them. This is exemplified in the case of Eastern European Jews, especially Ronne Kurlancheek’s grandparents, who arrived to the Greater Pittston area in order area to find work, raise a family, and worship. Many of these Jewish immigrant families arrived in the United States with nothing, worked hard in business, and thrived within the first and second generations. When many Eastern European immigrants faced adversity elsewhere in the US, Greater Pittston welcomed newcomers into their community and provided space where immigrant families could establish their own ethnic organizations and churches. Yet unlike other industrial areas of the US, the Greater Pittston area did not have a large African-American population during much of the twentieth century. For an industrialized area with mining and manufacturing, Greater Pittston ran counter to many other areas in the Rust Belt, which drew large amounts of African Americans who were looking for work. Therefore, Greater Pittston did not experience the Civil Rights movement to the same degree as other industrialized areas of the country. Still, the differences within the ethnic and religious makeup of Greater Pittston during the post-war period fostered an atmosphere of cooperation, competition, and numerous opportunities for success in business.

The Greater Pittston area of Pennsylvania has a dynamic unlike many other cities across the US This exhibit will showcase its unique qualities as well as connect it to the national narrative through the use of photographs, newspaper clippings, and oral histories in the collections of the Greater Pittston Historical Society. The four areas of focus for this exhibit are Entertainment and Leisure, Religion and Family Life, Business and Industry, and Patriotism and Politics. Life in post-World War II Pittston is an intricate and insulated web of ethnic and religious affiliations. This area boasts a strong sense of Patriotism with a tight grasp on native cultural customs, small business savvy and the big anthracite coal industry, and politics based on real work for the constituency. While Pittston follows the national trends in many ways — city-wide support for local sports, celebrating the Bicentennial commemoration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and the popular sleighing parties of the 1950s, for example — in other ways they did not fit into the narrative of their national counterparts. The Greater Pittston area and its residents resisted the propensity towards big business (i.e. shopping malls), the breakdown of religious fervor, and suburbanization. In their commitment to family, faith, and industry, the people of Pittston have proven not only resilient, but also rather independent to national trends in the postwar period.

—Patrick Gallagher and Nicole Negron

(Background image: Aerial view of Pittston, 1958. Sunday Dispatch Photographic Collection, Greater Pittston Historical Society, Pittston, PA)

This exhibit was made possible through the Student Summer Research Fellowship Program at Misericordia University, and was supervised by Dr. Jennifer Black during the summer months of 2015. Student contributors include Patrick Gallagher, Matthew Gromala, Anthony Mancini, Michael McDonnell, Nicole Negron, and Cody Spriggs.